A Bruegel of the Enlightenment

The Danish painter Jens Juel (1745–1802, fig. 1) is remembered today foremost as an eminent portrait painter, whose output deserves comparison with the production of the best contemporary colleagues in Europe, as the most recent monograph on the Danish painter attempts to do. In the subtitle, he is called “a European master” [1]. Nevertheless, Juel was also a productive and interesting landscape painter – in this regard, his oeuvre resembles that of his colleague Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) – but with certain exceptions, his contributions in this field have remained shamefully overlooked. A few studies in recent decades have shed light on Juel’s achievements as a landscape painter, and these form the starting point for the present article.

Yet equally overlooked are the figure groups and narrative scenes in Juel’s landscape compositions, which allow these works to also be classified as genre paintings. In fact, I will go a step further and consider several works by Juel as deliberate hybrids between landscape painting and genre painting. In any case, the narrative and emotional aspects of the figure groups in Juel’s landscape paintings are so striking that it makes little sense to regard these works as nature studies, just as idealization, which was otherwise central to pastoral landscape depictions, is also not a primary concern. Instead, Juel’s depictions of contemporary rural life (and other topographies) must be viewed from a broader perspective, across genres.

Although these works do not represent major compositional or thematic innovations, the contours of an artistic project emerge, drawing on both landscape and narrative elements, which may have been overlooked by art history precisely because they occupy a transitional space between genres as well as periods. While certain aspects of Juel’s artistic outlook place him in an Enlightenment mentality, other aspects point to his Sturm und Drang and proto-Romanticist leanings. And, as will be argued in what follows, his compositional strategy might embody a multilayered Romantic message in the making rather than a mere flight of fancy.

Biographical Sketch of Juel

First, we must briefly outline Jens Juel’s background and education. He was born in Balslev, on the island of Funen, in 1745, the son of a deacon and of a schoolmaster. He did not attend the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, which might seem surprising, but instead apprenticed with the painter Michael Gehrmann (1707–1770) in Hamburg from around 1760 to 1764–65. However, the journey south was not much farther than the journey to Copenhagen, and thanks to the Danish dominion over the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, there was lively cultural exchange between Denmark and northern Germany at this time [2].

With Gehrmann, Juel evidently became acquainted with the Dutch painting tradition, as seen in Juel’s moonlit scenes (Binnenalster in Hamburg, 1764, Hamburger Kunsthalle, fig. 2), which show knowledge of Aert van der Neer (1603–1677) [3]. Juel was back on Funen by 1765 at the latest, and from at least 1766, we find him enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where he won the small gold medal in 1767 and the large gold medal in 1771 for two history paintings. Juel was supposed to compete among the gold medal winners for the academy’s grand travel scholarship, but because a number of aristocratic patrons took it upon themselves to finance his journey, he withdrew from the competition [4].

In 1772, Juel embarked on a seven-year journey that took him via the familiar city of Hamburg to Dresden, where he trained under the portrait painter Anton Graff (1736–1813) until 1774. From there, he travelled to Rome, likely passing through Vienna and Venice. Strangely, few works are known from his time in Rome, although he painted a now-lost portrait of his colleague Nicolai Abildgaard (1743–1809). Perhaps Juel worked for the city’s leading portrait painter, Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787). In 1776, Juel appeared in Naples (together with Abildgaard), and that autumn he travelled to Paris with another colleague from Copenhagen, Simon Malgo (1745–after 1793). In the spring of 1777, Juel travelled with Malgo and the engraver Johann Friedrich Clemens (1748–1831) to Switzerland via Lyon, and Juel returned home via Kassel and Hamburg at the end of 1779. In Switzerland, he became acquainted with the pastel painter Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789). Juel returned to Copenhagen in the spring of 1780 [5].

Upon his return, Juel’s career as a leading portrait painter quickly gained momentum. He was immediately appointed court portraitist in 1780, became an associate at the Academy of Fine Arts the same year, and was admitted as a full member in 1782. He was appointed extraordinary professor at the Academy in 1784 and ordinary professor in 1786, serving as director of the Academy twice, from 1795–97 and 1799–1801 [6]. He did not marry until 1790, and when he suddenly died in 1802, he left behind a number of young children, two of whom later married the painter Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783–1853).

Types of Landscape Works in Juel’s Oeuvre

Juel’s stay in Geneva was a turning point in several ways and formative for his efforts in landscape painting. Not only did he become acquainted with a completely different topography than the Danish one, but he also found himself in a rich intellectual milieu centred around the naturalist Charles Bonnet (1720–1793), whose portrait he painted. Like other pioneers who were discovering aspects of nature that foreshadowed the Romantic artistic vision, Juel selected not only picturesque scenery but also natural phenomena, such as storms, where empirical interest took precedence [7].

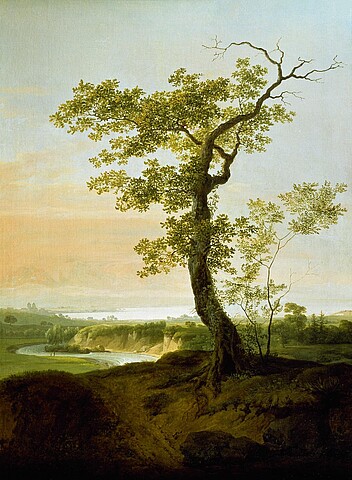

Depictions like View of the Lake Geneva Close to Veyrier (1777–79, Thorvaldsen’s Museum, fig. 3), where a solitary, twisted tree dominates the foreground as a dramatic repoussoir, while streams and lakes fade into the distance, are indebted to the Dutch school. Its interpreters, especially Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1629–1682) and his pupil Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709), had perfected this technique. Elements drawn from pastoral, Italianizing, and idyllic painting – with Nicolaes Berchem (1620–1683) as a model – can also be traced in Juel’s works, as he had the opportunity to study first-class examples from the Flemish and Dutch schools in the Moltke collection [8]. Some of Juel’s landscape paintings are directly modelled after works from the royal or other collections [9].

In other works – especially the later ones – figures grow in significance and placement, surpassing their role as mere staffage for aesthetic effect. View of Copenhagen, Taken near Fortunen (1790s, Øregaard Museum, fig. 4) shows a horse-drawn carriage moving through a hollow in the landscape. From the ridge, an attractive, portal-like view opens towards Copenhagen in the distant background, but the innovation in the painting lies in the nursing woman in the carriage, which, as a motif, seems to appear for the first time in Danish art. A freely roaming white milk cow with a recognizable udder is seen staring at the passing carriage from the left side of the painting, emphasizing the connection, centred on fertility, between humans, animals, and surroundings. The painting is symptomatic of Juel’s desire to depict peasants, riders (and other inhabitants of the landscape) in harmonious interaction with nature.

A third group of works includes studies of natural phenomena such as the northern lights, lightning, thunder, moonlight, etc., which also find their way into some of the genre-like works. A typical example is Landscape with Northern Lights. In the background, Middelfart Church. ‘Attempt to Paint the Northern Lights’ (1790s, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, fig. 5).

Common to these works is a contemporary tendency to compose several existing drawn sketches into one whole on the canvas. We are in the time before plein air painting, and the landscape scenes took shape in the studio, not outdoors [10] Therefore, memory and imagination naturally played key roles in Juel’s creative process.

Reception of Juel as a Landscape Painter

It cannot be claimed that Juel’s efforts as a landscape painter have been treated gently by Danish art history. Despite producing around 75 works in this genre [11], twentieth-century observers were not convinced of their value. In his dissertation on Danish landscape painting, Henrik Bramsen wrote:

“Juel’s landscape production is strongly characterized by a lack of planning; it possesses neither a line nor a guiding idea, not even the idea that a fully realized topographical landscape painting can provide. Most of the landscapes are likely based on personal experiences, in which he tried to express something he could not convey in his portraits. However, these seem to have been only fleeting moods, and there is no attempt to delve deeper into the artistic interpretation of the natural spectacles that captivated him. Although both painted and drawn studies of landscapes are known, there was hardly any in-depth nature study involved. In the landscapes, impersonal reminiscences of older art mix with direct observations. They confirm the contemporary statement that Juel only pursued landscape art ‘in his spare time and for pleasure’" [12].

The quote that Juel painted “for pleasure and in his spare time,” as it is more accurately phrased, comes from Niels Henrich Weinwich’s (1755–1829) lexicon of artists from 1811, making it the earliest assessment of Juel’s practice as a landscape painter [13]. The notion that Juel’s entire outlook was shaped by his naive, innocent character as nature’s cheerful son was cemented here, allowing him to serve as a contrast to his intellectual contemporary, Abildgaard. Likewise, Juel’s practice thus began to take on more of the character of personal amusement rather than a serious endeavour [14].

A closer look at the ownership of Juel’s landscapes (both during and after his lifetime) debunks this myth [15]. View of the Country near Jægerspris (1782, National Gallery of Denmark) and its pendant View from Sørup towards Fredensborg Castle (1782, Fuglsang Art Museum, fig. 6) were both found in Juel’s estate after his death. According to the dedications on two engravings by Frederik Ludvig Bradt (1747–1829) after the works, the intended buyers were Crown Prince Frederick and Dowager Queen Juliane Marie. Perhaps the coup in 1784, which removed these two royals from power, disrupted the delivery [16]. The work A View across Lac Léman towards Mont Blanc and Geneva (1777–78, National Gallery of Denmark) was purchased at Juel’s estate auction in 1803 by the courtier and landowner (and fellow Funen native) Johan Bülow (1751–1828). At Bülow's estate auction in 1829, it was bought by Juel’s fellow landscape painter Jens Peter Møller (1783–1854) on behalf of Prince Christian Frederik (later Christian VIII). The next owner in line was Dowager Queen Caroline Amalie. Other works were sought after by Juel’s artist friends as well as later artists. The aforementioned View of the Lake Geneva Close to Veyrier is symptomatic – it was Juel’s wedding gift to his friend Clemens, and the same Jens Peter Møller bought the painting at Clemens’ estate auction in 1832, from whom none other than Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844) purchased the painting for his collection in 1838 after returning to Denmark. As we will see, this was not Thorvaldsen’s only purchase of a Juel landscape.

As we can observe, Juel’s landscapes were popular among the royal family, the nobility and artist colleagues, and they continued to be so well into the nineteenth century. When art historians have previously struggled to pinpoint a project within Juel’s landscape pieces, it is due to the fact that very few records, such as letters, have survived from Juel himself to shed light on his thoughts and sources of inspiration. Only the inventory list of what he owned at his death provides some information.

Two Paintings from Middelfart in Juel's Estate

Upon his death in 1802, Juel left behind two landscapes that are pendants to each other: View of the Little Belt from Hindsgavl on Funen (c. 1800, Thorvaldsen’s Museum, fig. 7) and View of the Little Belt from a Hill near Middelfart (ditto, fig. 8). The paintings were included in his estate auction in 1803, where they were purchased by the engraver Gerhard Ludwig Lahde (1765–1833), who, like many others of his generation, had immigrated from Germany. In 1843, the paintings were sold by Lahde’s daughter to Thorvaldsen, which is why they can now be seen at the museum dedicated to him in Copenhagen.

The paintings can be localized to the vicinity around the manor Hindsgavl, even though the manor house itself is not visible in the paintings. The main building at Hindsgavl was constructed in 1784 in the Louis Seize style by the local architect Hans Næss (1723–1795), who had been a student of the groundbreaking Neoclassicist Nicolas-Henri Jardin (1720–1799) at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. The builder was chamberlain and cavalry officer Christian Holger Adeler (1743–1801), who came into possession of the estate through his wife, Karen Basse Fønss (1747–1808).

The Danish art historian Anders Kold presented a convincing analysis and interpretation of the two landscape pieces as moralizing landscapes as early as 1989, and my presentation here owes a debt to Kold’s pioneering efforts. The same can be said of Anne-Christine Løventoft-Jessen’s exploration of the acute observations of nature present in Juel’s paintings. My efforts here aim to both expand on their conclusions, particularly in an aesthetic sense, and to further understand the works as genre paintings.

The works are not dated, but as Kold points out, Juel was visiting his hometown, the village of Gamtofte, in July 1799 for his mother’s funeral, and it is known that he also took the ferry across the Little Belt to visit potential clients and make studies. It is likely that he passed by Hindsgavl during this trip and received the commission then. Not only the subject matter of the paintings but also the fact that there are copies of them at Hindsgavl, painted by Carl Frederik Vogt (1781–1834) around 1810, supports this assumption. At the same time, as Kold notes, the two pendants could not have been intended as overdoor paintings for the manor, as their dimensions are too small to serve this purpose.

Christian Holger Adeler died in 1801 and Juel in 1802. Perhaps the works were not quite finished at Adeler's death, which is why they remained in Juel’s studio. The fact that Juel’s widow inherited them may be due to no advance payment having been made.

Two Manor Paintings without a Manor

Now to the works themselves and their compositions. View of the Little Belt from Hindsgavl on Funen immediately strikes the viewer with a strong contrast effect, where the terrain in the foreground lies in darkness, the terrain in the middle ground is illuminated, while the background consists of the likewise illuminated water surface of the strait. Two steep slopes and two tall, slender, upright trees frame the scene like a portal to the water, while two roads wind symmetrically up the hills. In the foreground, slightly to the right, we see a riding master berating a peasant who carries a rake, gesturing at him with an outstretched arm. Immediately behind these figures, in the illuminated middle ground, sits a conversing elegant couple on a white bench in the sunshine. The woman holds a parasol while her male companion sits sideways, relaxed, with his arm resting on the back of the bench. In the same illuminated zone, but now on the left side of the painting, a larger group of figures can be seen, where a strolling couple to the left, arm in arm, enjoys the view over the strait, while another group to the right consists of a standing woman with a parasol and two children, one of whom bends down to play with a dog while a boy sits on the grass and gestures. Behind all these well-dressed figures on the walking path is a white-painted picket fence, and over a low vegetation, the strait and the surrounding distant landscape meet us, while a solitary sailboat is seen on the still sea.

The pendant View of the Little Belt from a Hill near Middelfart exhibits both similarities and differences in relation to its counterpart. This work also features a classic division into foreground, middle ground and background, but the contrasts are significantly softened, so that the transitions between them occur imperceptibly. Here it makes more sense to start from the background, which exhibits the most similarities with the pendant painting. Here we see the Little Belt, its course bending in a gentle curve from right to left. A solitary sailing ship can be seen on the surface of the sea. Along the transition to the middle ground, we find a prospect of the town of Middelfart, whose church tower rises prominently above the building mass, and the middle ground consists of lush fields, whose expanse is interrupted by a winding road, which can be traced by its full-lined alleys. This country road continues into the foreground, where its gravel surface becomes visible; the road is no longer framed by an avenue, and it changes direction so that a gentle curve to the left counterbalances the avenue’s counter-movement to the right in the middle ground. A gate to the left in the foreground forms a boundary between the foreground and middle ground, which is visually supported by a stone wall to the right of the gate and a bushy hedge to the left, which carries on the road’s earlier winding to the left, although it separates itself from the actual road in the foreground. In addition to the gravel road, the foreground consists of lawns. A peasant girl has opened the gate with her left hand while holding a rake in her right. Into the foreground, two well-dressed gentlemen ride on horseback, the front one dressed in black on a brown horse, while the one behind is dressed in red and on a white horse. In the opposite right side of the foreground, a seated man with his walking stick takes a rest in the edge of the ditch, while two children to the left of him, a sitting boy and a standing girl, are about to go home, with her pulling the boy by the arm while she points towards the gate.

The first thing one notices when encountering Juel’s complementary works is an absence, namely the absence of the manor house itself – Hindsgavl – as a motif. Although quite newly built and monumental, Juel has evidently chosen to omit the main attraction. This was certainly the case until a third prospect by Juel (in private ownership) surfaced, as it shows the manor standing in the landscape, seen from the garden side from a distant position on the island of Fænø in the Little Belt. However, the picture is smaller than the other two and has a different provenance [17].

In the two pendant works, Juel thematically circles around the estate’s boundaries to the outside world, namely where its lands border the strait and the town. The former painting, View of the Little Belt from Hindsgavl on Funen, clearly depicts the conclusion of a garden layout, as the entire layout is mirror-symmetric. Not only do the upright trees flank the attractive view towards the strait strategically; the paths that wind up the hills on either side are obviously human creations serving the pictorial beauty. The bench where the conversing couple sits stretches not only across the entire width of the passage but is also concave, providing a spectrum of viewing angles towards the vista, as if it were a polished lens of the same shape. Similarly, the two slopes testify to a desire to frame and concentrate the view towards the strait from the manor house, which we can only imagine.

The second painting, View of the Little Belt from a Hill near Middelfart, is presumed to depict the territorial boundary of the estate against the town in the form of the stone wall and gate that regulates access. Among the two riders, the lord Adeler himself can be seen, thereby, as Kold notes, thematizing the landowner as a patron of his local town. Adeler had indeed established both a brickyard, a weaving mill, and a clothing factory in Middelfart [18].

An Allegory of the Peasants’ Liberation in the Spirit of the Enlightenment

As Anders Kold argues, Juel’s two depictions can be interpreted as a manifesto in support of the land reforms, including notably the abolition of the stavnsbånd (a form of serfdom), which was effectuated in Denmark from 1784 onwards. Christian Holger Adeler belonged to the group of reform-minded landowners, although he was a lesser figure within this group, whose leading agents were Counts Christian Ditlev Frederik Reventlow (1748–1827) and Andreas Peter Bernstorff (1735–1797). Other driving forces were officials such as Christian Colbiørnsen (1749–1814). Adeler implemented land consolidation on his estates from 1787 to 1796, and he unequivocally supported the new movement, especially the abolition of the stavnsbånd, with his writing from 1787, Allehaande Tanker i Anledning af Hr. Conferenceraad Bangs Afhandling om Bondestanden (Various Thoughts on Mr. Councillor Bang’s Treatise on the Peasant Class) [19].

But Juel himself also seems to have been both well-informed about and sympathetic to the new political winds blowing across the country. He was a member of both Masonic lodges and patriotic as well as literary societies, where he mingled with the era’s leading intellectuals from the bourgeoisie, including Colbiørnsen and Tyge Rothe (1731–1795) [20]. A major work that sparked the reform movement was indeed Rothes’ not-so-easily-titled work Danske Agerdyrkeres — især den til Hovedgaarden hæftede Fæstebondes Kaar og Borgerlige Rettigheder, for saavidt samme ere bestemte ved Lovene, eller Vort Landvæsens System, som det var i 1783, Politisk betragtet (Danish Farmers — Particularly the Tenant Farmer’s Conditions and Civil Rights as Determined by the Laws, or Our Agricultural System as it Was in 1783, Politically Considered), and Juel owned the book, which we know from the catalogue of his estate auction in 1803 [21]. Adeler must have had similar knowledge, for although the title does not appear in a catalogue of the library at Hindsgavl from 1808, he refers to Rothes’ book in his own treatise [22].

Other indications also suggest that Juel’s efforts as a landscape and genre painter can be read into the programme of the land reforms. We know that during his stay on Funen in 1799, Juel visited the estates of Hagenskov and Sanderumgaard, as shown in a letter from his friend, Pastor Bierfreund, to Juel’s wife, where he asks her to be patient, as Juel is to visit the merchant Ryberg and courtier Bülow [23]. Niels Ryberg is known today as the commissioner of the major work The Ryberg Family Portrait (1796–97, National Gallery of Denmark). But particularly the client-artist relationship between Johan Bülow and Jens Juel is interesting and a good indicator that Juel’s depictions of peasant life were not only beautiful landscape scenes but also carefully thought-out symbolic compositions. Although Bülow later opposed the more extensive reforms of the time after the coup d’état in 1784, which he himself had helped to enact, he presented the following day after the coup to Crown Prince Frederik (VI), now the country’s real ruler, the manuscript En tro Tieners Tanker til hans kiere Herres nær mere Eftertanke (Thoughts of a Faithful Servant for His Beloved Master for Further Reflection, 1784), in which he advocates for peasant liberation. Ten years later, in 1794, Bülow appears as the purchaser of Juel’s A Storm Brewing behind a Farmhouse in Zealand, 1791–93, National Gallery of Denmark, fig. 9), which depicts the farm Eigaard near Ordrup. This is not just any farm, but the first farm that was relocated under the estate Bernstorff in Gentofte [24]. Similarly, the surveyor and scientist Thomas Bugge (1740–1815) appears as the owner of one of Juel’s farm paintings from the Gentofte region, and he was directly involved in implementing the land reforms through his measurements [25].

Finally, a previously overlooked aspect of Juel’s practice confirms his connection to an empirical and Enlightenment-oriented worldview. As Løventoft-Jessen has documented, Juel was also a member of a society for natural history, which had not previously been known. Furthermore, the members of this society undertook extensive trips through the Danish landscape. Moreover, there are identifiable representations of plants from the Danish flora in almost all of Juel’s landscape paintings, and this practice is unique to Juel and is not seen among his contemporary European colleagues [26]. Juel’s involvement in nature as a phenomenon thus occurred through many avenues and on levels ranging from the abstract to the concrete.

Learning from England? The Impact of the Picturesque

Juel was not an artistic pioneer, as contemporary art historians have noted about him, and I will not dispute this statement here (except for the fact that his studies of meteorological phenomena can be considered innovative and proto-Romantic) [27]. Nevertheless, his contributions to landscape art have all too often been perceived as a typical, somewhat unoriginal attempt rather than as a pictorial project with certain independent anchors of both compositional and thematic nature.

I have already outlined how both direct and indirect sources draw a compelling picture of Juel as a man of progress, who both oriented himself towards and commented on the land reforms that he witnessed transforming the Danish landscape in the few decades leading up to the end of the eighteenth century. His presence in Switzerland at the right time and place clearly laid the foundation for his intellectual development and outlook, and when his entire oeuvre is often read in a spirit of freedom (or spontaneity), it concerns not just painting technique or fashion, but also a worldview. Therefore, one finds in his oeuvre a use of landscape as a tool for characterization, ranging from the pleasingly vernacular (as in The Dancing Glade at Sorgenfri, c. 1800, National Gallery of Denmark, fig. 10) to the symbolically calculated (as in A Running Boy. Marcus Holst von Schmidten, 1802, National Gallery of Denmark, fig. 11). In the latter, the student is seen running freely and pointing to his progressive reform-pedagogical school in the background – not exactly a conventional motif for a nobleman’s portrait [28]. In Juel’s library, for example, were found Voltaire’s (1694–1778) Précis du siècle de Louis XV and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (1712–1778) Confessions (in Danish translation) [29].

Juel never went to England, but as a true artistic cosmopolitan, he absorbed innovations from the English school vicariously [30]. England was a European powerhouse for graphics, so it was not difficult to obtain engravings after famous English paintings, and they also appear in Juel’s estate [31]. In Switzerland, he must have adopted the era’s new craze for the conversation piece, as seen in a number of portraits of distinguished people sitting in the open air [32]. He applied the same treatment to the largest and most ambitious of his Danish aristocratic and noble portraits – most iconically in the aforementioned painting of the Ryberg family. Kold argues that Juel must have encountered William Hogarth’s (1697–1764) influential treatise as early as his first years in Hamburg, where it was, in translation, the latest trend in art theory, and knowledge of Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) and the Venetian veduta painting can also be substantiated [33]. Juel’s landscapes-as-genre-pieces or genre-pieces-as-landscapes synthesize all these impressions in continuation of the Dutch inspiration.

In contrast, his lighting is aesthetically forward-looking. In his typical landscape pieces, Juel keeps the middle ground illuminated, while the other areas are darker. There is nothing new in this [34]. Generally, however, he bathes both landscape and figures in a soft, uniform light that does not differentiate by social status among the participants [35]. Yet in these two Hindsgavl works, he uses temporal extremes of the day to symbolically signal the progression of enlightenment across the landscape [36]. In this way, he unites ancient pictorial virtues with a budding Romantic use of lighting, which Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), an avid admirer of Juel’s landscapes, brought to its climax [37].

Two observations from Kold’s commentary are central to a deeper understanding of Juel’s hybrids of landscapes and genre pieces: “The figures conform with a regularity that rejects extreme incidents, and as for the figuration, the potential for movement is measured to an absolute minimum.” He continues: “In both works, also compared as pendants, an aloofness from reality is traced. A direct and unreserved encounter is avoided.” Whether the works from the Hagenskov region belong to the Rococo, as Kold demonstrates, is of less interest here [38]. Hogarth’s The Analysis of Beauty (1753, fig. 12) heralded the so-called picturesque craze in English painting and garden art in the second half of the eighteenth century, and much suggests that Juel’s project can be read into this aesthetic category, even though he never set foot on English soil, let alone in a Romantic garden there.

View of the Little Belt from Hindsgavl on Funen is fundamentally a vista, and the narrowing of the field of vision due to the flanking earthen mounds gives – along with the marked darkening of the foreground – a telescope-like effect. At first glance, one might think the work is more Baroque than Romantic (incidentally, this was also Bramsen’s verdict of Juel) [39]. However, other elements point towards the picturesque aesthetic, whose compositional demands, according to aesthetician Jacques Rancière, stipulate that “the gaze must be bounded in a way that does not allow it to see the limit of what it is looking at. There must be a limit that conceals the limit”[40]. In Juel’s work, all transitions from foreground to middle ground and further to background are softened or erased. The shadow in the foreground raises doubts about the accuracy of the topography; the bench in the zone leading to the middle ground is half concealed by the foreground’s earthen mound; the picket fence, which should otherwise allow a partial view of the strait’s water surface, is blocked by vegetation; and an almost improvised little fence to the right up the slope manages to block the transition between both the foreground and the background landscape as well as the water in between. This practice was endorsed by Hogarth under the term intricacy, and later Sir Uvedale Price (1747–1829) defined this effect as “that disposition of objects which, by a partial and uncertain concealment, excites and nourishes curiosity”[41].

A more direct inheritance from Hogarth meets the viewer in View of the Little Belt from a Hill near Middelfart, where the various horizontal layers in the composition are bound together by an S-shaped curve, which also constitutes a sort of procession axis in the image. This serpentine was the cornerstone of Hogarth’s ideal of beauty, as it could act as a link between nature and culture, just as its primary merit was the achievement of variety – as both announced and shown on the cover of his treatise. If the two complementary works, as Kold claims, are an allegory of the gradual path to liberation in the countryside, this occurs not only as a movement from darkness to light but also as a transition from the Baroque garden ideal to the Romantic. The S-shape can easily be related to the Rococo, but the theoretical framing it received from Hogarth is just as much a philosophy of freedom as it is of beauty. Spontaneity equates to naturalness, and the path to it did not follow a straight line, but rather an alternating curve. Art historians have frequently regarded naturalness as Juel’s hallmark, but without perceiving it as aesthetically symbolic [42].

Furthermore, in this work, we again see a use of strategic concealment as a means towards variation: Large portions of the road cannot be seen directly but can only be determined through adjacent landscape elements, and even the stone wall in the foreground is half hidden by vegetation. Although the sunny, wide-open scenery, where the sunbeam just falls in the foreground on the riders and beyond, is free from dramatic shadows, the transitions in the landscape are subtly eluded. In the same way, the silhouette of rooftops in the town of Middelfart almost completely blocks the transition from land to sea.

This practice is not reserved solely for landscape elements in Juel’s paintings. In Landscape by the Sound (c. 1800, Nivaagaard Collection, fig. 13), where the summer residence Aggershvile to the right is relegated to being just one among many subordinate elements in the painting, the winding road is again seen as a structuring element, but even more telling is the preference for allowing partially illuminated groups of figures – peasants resting to the left, the gentry likewise to the right – to flank the road in a dynamic way, whereby their gestures serve both local and universal functions in the painting. The groups of figures are internally bound together by relations of attention and touch, while together they also manage to clarify the foreground as a bowl-shaped depression in the fields. Their activities provide a horizontal counterweight to the winding trajectory of the road deeper into the middle of the painting.

Conclusion: The Art of Sympathy

In the wake of the focus from art historians like Michael Fried and Wolfgang Kemp, art history has increasingly concentrated on the reception-aesthetic aspects of art in the early modern period. This has likely enabled us to discover aspects of, for example, eighteenth-century works that did not fit within the traditional aesthetic of beauty, which perpetuated a conventional, academic normativity, nor could they be captured by the iconological approach, which operated on the internal premises of the work. This newfound receptivity can also provide us with access to Juel’s painterly project of hybridity.

Juel’s most sophisticated attempts within the hybrid of genre painting and landscape painting inscribe themselves in an interesting and unique way in the many cultural upheavals of the eighteenth century. We have already established that the lighting in Juel’s works points forward to Romanticism, while his precise use of plant motifs has its roots in the Enlightenment project. But like the pioneer of genre painting, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525/30–1569), Juel depicts peasants at rest rather than at work, which does not constitute a renewal of the repertoire [43]. The integration of the peasants into the landscape as a marker of their naturalness is also not a new approach.

However, the concept of work is nevertheless the key to understanding Juel’s project on canvas. First, the resting and contented peasants are no longer depicted with exaggerated physiognomies bordering on pure caricature, as was the case in the tradition from Bruegel to Adriaen Brouwer (c. 1605–1638), Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685), and David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690) [44]. The figures are also not depicted in a drunken, dishevelled, or lewd state but as being in balance with both themselves, their close relationships, and their natural surroundings. The peasant class as a cultural otherness has, in other words, been repressed from Juel’s depictions of this already 200-year-old repertoire. In Landscape by the Sound, both the burghers and the farmers are placed on equal footing and in the same state, which is also true for Emilie Kilde (1784, Art Museum Brandts, fig. 14), which depicts people gathered around a spring housed in a monument [45]. The common people are depicted with undivided sympathy and are never the object of ridicule. This development could already be traced in a painter like van Ostade, whose long career shows a shift in the depiction of peasants from coarse caricature with high drama to sympathetic engagement characterized by calm and harmony [46]. However, the landscape in van Ostade’s works has not yet been endowed with modern allegorical significance – that required a changed perception of nature.

As Løventoft-Jessen points out, Juel had to break the pastoral convention, which he was intimately familiar with and had himself experimented with (A Mountainous Landscape with a Waterfall. Sunrise, 1790, National Gallery of Denmark, fig. 15), in order to express the new patriotic ideals of the time [47]. However, one should not harbour illusions that the patriots of the time – and the societies of which they (including Juel) were members – aimed to abolish class distinctions between the bourgeoisie and the peasantry. Instead, the aim was to form and educate the peasant [48]. Nevertheless, in Landscape by the Sound, the peasant boy to the left of the image gestures that he wants to stray to the right in order to play with the bourgeois girl. In harmony with other compositional choices in the painting, this highlights the point that the landscape can make possible the overcoming of class differences – at least for a moment [49].

Secondly, the absence of labour (in nature as a context) also has aesthetic implications. As is well known, it was a cornerstone of the understanding of art, as it developed after the Renaissance and within the academies, that the fine arts did not serve practical purposes. Hence the difference between painting and sculpture on the one hand and architecture (and other ‘mechanical arts’) on the other. As Rancière points out, Charles Batteux (1713–1780) enshrined this dictum in 1746 in his treatise Les beaux arts réduits à un même principe [50] Furthermore, the fine arts were characterized by imitating nature, while the mechanical arts consumed nature instead [51]. Finally, the fine arts aimed to achieve beauty that could promote pleasure.

Rancière unfolds the paradox that arose when this philosophy of art confronted the aesthetic innovation of the time, the English landscape garden. For what aesthetic status does the art of gardening acquire when the very act of manipulating nature, in principle, excludes it as a free art form – and when the principle of imitation is replaced by intervention? At the same time, the meaning of the word ‘nature’ shifted from denoting an invisible principle that governed everything in the universe to a much more down-to-earth meaning – in the literal sense of the word [52]. In Rancière’s words:

“The art of imitation had to have the same allure of freedom and ‘ease’ of nature, which manifests neither will nor labor in how it produces its effects. That art had to imitate nature as a (necessary) cause and as a (free) effect. This balance is broken when nature itself becomes an artist, and when its art manifests itself as the creation of scenes that combine trees, water streams, and stones with the play of light and shadow. Thenceforward, nature meant, essentially, freedom” [53].

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Juel’s project, where peasants inhabit the picturesque nature, thematizes freedom – and this in several dimensions, ranging from the abstract to the concrete: freedom from serfdom, freedom to express one’s individual temperament, and freedom in the form of nature’s autonomous, cyclical creation, which transforms with the changes of the seasons and weather, the dynamics of the streams, and the budding and wilting of the flora. The genre pieces of the seventeenth century, both Flemish and Dutch, were animated by a view of work and nature, where the lives of peasants and fishermen were morally commendable because they did not profit from the trading process but merely provided the fruits of nature’s ‘labour.’ Conversely, occupations in the cities, which involved both refinement and the achievement of surplus value, and which engaged in transactions with money as a medium of exchange, were met with varying degrees of scepticism or condemnation [54]. With his unequivocal interest in rural life, Juel thus inscribes himself in an old tradition, where it is clearly not the food products but the landscape as a collective stage that integrates humanity concretely and symbolically into the environment that captivates the painter.

One of the standard bearers of the picturesque movement, Sir Uvedale Price, comments in his treatise Essay on the Picturesque, As Compared with the Sublime and The Beautiful (1794) on a painting by Philips Wouwerman (1619–1668) depicting a cartload of manure as proof that painting can refine its subject matter in a way that sculpture cannot achieve [55]. Indirectly, Price also acknowledges genre painting’s effect on the art perception of his time towards an expanded aesthetic awareness – and not just an expanded understanding of nature. This was about cultivating a new way of seeing, both in concrete and abstract terms, aimed at aesthetic education [56].

As Michelle Facos asserts, Romanticism is an inherently conflicting notion, and it overlaps in certain respects with Neoclassicism [57]. Still, the renegotiation of the concept of nature lies at the heart of Romanticism. If we merely focus on the possible relationship to nature cultivated by artists, and if we also take into account the claim made by Rancière that the core of the craze for the Picturesque manifested itself as a new sense of nature as freedom (and not as mere whimsiness), it turns out that Jens Juel has his fair share of the Romantic impulse after all. In fact, his contributions to a Romanticism avant la lettre manage to imbue nature with several layers of connotations, and in some respects his hybrid creations convey a more complex view of nature than many a canonical Romanticist painting.

As we have seen, Juel – with his original combinations of genre and landscape painting – can be viewed as an active participant in the cultivation of a new way of seeing, which renewed European aesthetic culture in just a few decades and paved the way for Romanticism. On Juel’s bookshelf stood the very manifesto of Romanticism, Herzensergießungen eines kunstliebenden Klosterbruders (1796) by Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder (1773–1798) and Ludwig Tieck (1773–1853), indicating that the Danish painter was already attuned to an era that he himself was only to experience the advent of [58].

Notes

[1] Thyge Christian Fønss-Lundberg, Anna Schram Vejlby: Jens Juel: En europæisk mester, Copenhagen 2021. Nevertheless, the monograph has, strangely enough, not been translated into English.

[2] Claus M. Smidt: Af hjertets lyst: Jens Juels landskabsmalerier, Nivå 1989, n.p.

[3] Ellen Poulsen: Jens Juel 1: Katalog. Catalogue, Copenhagen 1991, p. 30; Kasper Monrad: Jens Juel, Copenhagen 1996, p. 6–7.

[4] Fønss-Lundberg, Vejlby: Jens Juel, p. 14–16, 23, 26, 32.

[5] Ibid., p. 58–101.

[6] Ibid., p. 105.

[7] Anne-Christine Løventoft-Jessen: “Kunstneren Jens Juel og det videnskabelige blik på naturen”, in: Sjuttonhundratal: Nordic Yearbook for Eighteenth-Century Studies (2013), p. 156–168.

[8] Poulsen, Jens Juel 1, p. 15.

[9] Ibid., p. 200.

[10] Monrad, Jens Juel, p. 24–28, 37.

[11] Henrik Bramsen, Landskabsmaleriet i Danmark 1750-1875: Stilhistoriske hovedtræk, Copenhagen 1935, p. 23.

[12] Ibid. (my translation).

[13] Niels Henrich Weinwich: Maler-, Billedhugger-, Kobberstik-, Bygnings- og Stempelskiærer-Kunstens Historie i Kongerigerne Danmark og Norge, samt Hertugdømmene, under Kongerne af det oldenborgske Huus, med en Indledning om disse Kunsters ældre Skiæbne i samme Riger, Copenhagen 1811, p. 187 (my translation), accessible via https://www.kb.dk/e-mat/dod/130020876159.pdf.

[14] Anders Kold: “Ej blot af lyst og i ledige stunder: To landskaber af Jens Juel på Thorvaldsens Museum”, in: Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum (1989), p. 44, accessible via https://arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/artikler/ej-blot-af-lyst-og-i-ledige-stunder-to-landskaber-af-jens-juel-paa-thorvaldsens-museum.

[15] Monrad: Jens Juel, p. 39.

[16] Smidt: Af hjertets lyst, n.p.

[17] Birgitte Zacho: “Landboreformer: Katalog 23–29” [Kat. 24–26], in Aftenlandet: Motiver og stemninger i dansk landskabsmaleri omkring år 1800, ed. by Gertrud Hvidberg-Hansen, Stig Miss and Birgitte Zacho, Copenhagen/Odense 2011, p. 86–88.

[18] Kold: “Ej blot af lyst og i ledige stunder”, p. 47.

[19] Ibid., p. 46.

[20] Anne-Christine Løventoft-Jessen: “Juels patriotiske idyller”, in: Aftenlandet [see note 17], p. 79–82.

[21] Charlotte Christensen: “Jens Juels dødsboauktion”, in: Hvis engle kunne male… Jens Juels portrætkunst, ed. by Charlotte Christensen, Hillerød/Copenhagen 1996, p. 125.

[22] Kold: “Ej blot af lyst og i ledige stunder”, p. 46.

[23] Ibid., p. 49.

[24] Ibid.; Else Kai Sass: Lykkens Tempel: Et maleri af Nicolai Abildgaard, Copenhagen 1987, p. 311, n. 89; Kasper Monrad, “Caspar David Friedrich og Danmark”, in: Caspar David Friedrich og Danmark: Caspar David Friedrich und Dänemark, ed. by Kasper Monrad, Copenhagen 1991, p. 188.

[25] Stig Miss: “Landboreformer: Katalog 23–29”, in: Aftenlandet [see note 17], p. 91f.

[26] Løventoft-Jessen: “Kunstneren Jens Juel og det videnskabelige blik på naturen”, p. 145, 148f.

[27] Ibid., p. 145.

[28] Monrad: Jens Juel, p. 48; Fønss-Lundberg and Vejlby: Jens Juel, p. 203.

[29] Charlotte Christensen: “Jens Juel som kunstsamler”, in: Hvis engle kunne male… [see note 21], p. 114.

[30] Fønss-Lundberg and Vejlby: Jens Juel, p. 146f.

[31] Christensen: “Jens Juel som kunstsamler”, p. 114.

[32] Fønss-Lundberg and Vejlby: Jens Juel, p. 146f.

[33] Kold: “Ej blot af lyst og i ledige stunder”, p. 52.

[34] Monrad: Jens Juel, p. 51.

[35] Løventoft-Jessen: “Juels patriotiske idyller”, p. 83.

[36] Zacho: “Landboreformer”, p. 88.

[37] Gertrud Hvidberg-Hansen: “Naturen – besjælet og betragtet: Katalog 9–15”, in: Aftenlandet [see note 17], p. 67.

[38] Kold: “Ej blot af lyst og i ledige stunder”, p. 52 (my translation).

[39] Bramsen: Landskabsmaleriet i Danmark 1750-1875, p. 24.

[40] Jacques Rancière: The Time of the Landscape: On the Origins of the Aesthetic Revolution, trans. Emiliano Battista, Cambridge 2023 [Paris 2017], p. 49.

[41] Uvedale Price: An Essay on the Picturesque, as Compared with the Sublime and the Beautiful; And, on the Use of Studying Pictures, for the Purposes of Improving Real Landscape, London 1794, p. 18.

[42] As in this case: Anne Grethe Uldall: “Der hvor himlen aldrig er blå”, in: Meddelelser fra Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek 52 (1996), p. 154.

[43] Løventoft-Jessen: “Juels patriotiske idyller”, p. 82.

[44] Wayne E. Franits: Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting: Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution, New Haven 2004, p. 35, 41f, 55.

[45] Løventoft-Jessen: “Juels patriotiske idyller”, p. 82.

[46] Wayne Franits: “Domesticity, Privacy, Civility, and the Transformation of Adriaen van Ostade’s Art”, in: Images of Women in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art: Domesticity and the Representation of the Peasant, ed. by William U. Eiland and Patricia Phagan, Georgia 1996), p. 4–6.

[47] Løventoft-Jessen: “Juels patriotiske idyller”, p. 83.

[48] Løventoft-Jessen: “Juels patriotiske idyller”, p. 81–84.

[49] Nils Ohrt: “Døden i lykkelandet: Jens Juel ved Øresundskysten”, in: Aftenlandet [see note 17], p. 118f.

[50] Rancière: Time of the Landscape, p. 5.

[51] Ibid., 6.

[52] Ibid., 14.

[53] Ibid., 16–17.

[54] Peter van der Coelen, Friso Lammertse, and Lynne Richards (translator): “Bosch to Bruegel: Uncovering Everyday Life”, in: Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 11,1 (2019), p. 27f.

[55] Uvedale Price: Essays on the Picturesque, as Compared with the Sublime and the Beautiful; And, on the Use of Studying Pictures, for the Purposes of Improving Real Landscape, London, 1810), p. 2:xiv.

[56] Rancière: Time of the Landscape, p. 43.

[57] Michelle Facos: An Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art, New York 2011, p. 78, 81, 109.

[58] Christensen: “Jens Juel som kunstsamler”, p. 114.

Der wissenschaftliche Impuls ist unter folgendem Link dauerhaft abrufbar:

10.22032/dbt.64195

Figure 1: Jens Juel, Self-portrait, 1766. Oil on canvas, 34.3 cm × 42.6 cm (KS 93), Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art

Figure 2: Jens Juel, The Binnenalster in Hamburg, 1764. Oil on oak panel, 29.9 cm × 38.5 cm (HK-453), Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Image courtesy of Hamburger Kunsthalle

Figure 3: Jens Juel, View of the Lake Geneva Close to Veyrier, 1777–79. Oil on canvas, 116.4 cm × 86.9 cm (B239), Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of Thorvaldsen’s Museum

Figure 4: Jens Juel, View of Copenhagen, Taken near Fortunen, 1790s. Oil on canvas, 42 cm × 52 cm, Øregaard Museum, Hellerup. Image courtesy of Øregaard Museum

Figure 5: Jens Juel, Landscape with Northern Lights. In the background, Middelfart Church. ‘Attempt to Paint the Northern Lights’, 1790s. Oil on canvas, 31.2 cm × 39.5 cm (MIN 1936), Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Figure 6: Jens Juel, View from Sørup towards Fredensborg Castle, 1782. Oil on canvas, 60.6 cm × 77.5 cm (156), Fuglsang Art Museum, Toreby. Image courtesy of Fuglsang Art Museum

Figure 7: Jens Juel, View of the Little Belt from Hindsgavl on Funen, c. 1800. Oil on canvas, 42 cm × 62.5 cm (B237), Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of Thorvaldsen’s Museum

Figure 8: Jens Juel, View of the Little Belt from a Hill near Middelfart, c. 1800. Oil on canvas, 42.3 cm × 62.5 cm (B238), Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of Thorvaldsen’s Museum

Figure 9: Jens Juel, A Storm Brewing behind a Farmhouse in Zealand, 1791–93. Oil on canvas, 43 cm × 61 cm (KMS137), National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Denmark

Figure 10: Jens Juel, The Dancing Glade at Sorgenfri, c. 1800. Oil on canvas, 42 cm × 61 cm (KMS7661), National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Denmark

Figure 11: Jens Juel, A Running Boy. Marcus Holst von Schmidten, 1802. Oil on canvas, 180.5 cm x 126 cm (KMS3635), National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen. Image courtesy of National Gallery of Denmark

Figure 13: Jens Juel, Landscape by the Sound, c. 1800. Oil on canvas, 55 cm × 76 cm (0206NMK), Nivaagaard Collection, Nivå. Image courtesy of the Nivaagaard Collection