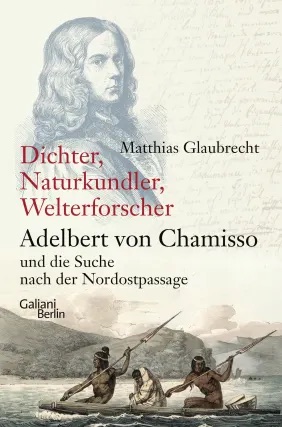

Matthias Glaubrecht

Dichter, Naturkundler, Welterforscher

Adelbert von Chamisso und die Suche nach der Nordostpassage

Many distinguished naturalists of the early 19th century have, through no fault of their own, faded from public view, overshadowed by more prominent contemporaries. This is particularly true for the French-German poet and naturalist Adelbert von Chamisso, who stands in the shadow of figures like Goethe and the early Romantics as a poet and Buffon and Alexander von Humboldt as a naturalist. Against this backdrop, Matthias Glaubrecht’s recent biography Dichter, Naturkundler, Weltenforscher. Adelbert von Chamisso und die Suche nach der Nordostpassage seeks to reintroduce the voyager to contemporary audiences. The book presents Chamisso not only as an extraordinary figure but also as a prism through which to examine scientific practices, cultural milieus, and intellectual networks of the early 19th century. While Glaubrecht achieves this in most parts of the book with a commendably accessible writing style, the biography’s emphasis on Chamisso’s uniqueness sometimes overshadows the chance to provide a more differentiated reflection on the culture and naturalists of his era.

At the heart of Glaubrecht’s work is Chamisso’s journey aboard the Russian sloop Rurik (1815–1818), exploring the unique voyage around the world as well as the complex social constellation and tensions on board the ship. The recent edition of Chamisso’s travel diaries, edited by Monika Sproll, Walter Erhart and Matthias Glaubrecht (V&R unipress, 2023), brought renewed attention to this pivotal period in Chamisso’s life. Glaubrecht’s biography builds on this edition, offering a close, if not first-person perspective on the naturalist’s experience. His approach seeks to familiarise a broader audience – particularly readers less familiar with the history of science – with Chamisso’s perspective, work, and the scientific collections and archival sources he left behind.

Glaubrecht focuses on Chamisso’s engagement with nature, especially botany and zoology, and explores his interactions with contemporaries like Alexander von Humboldt, Rahel Levin, and Otto von Kotzebue, son of the famous poet August von Kotzebue. Especially the interplay between Chamisso and his captain, Otto von Kotzebue, provides a compelling narrative thread that illustrates how Chamisso’s poetic ambitions influenced his work and identity as a naturalist, as Glaubrecht reconstructs the tension between Chamisso and Kotzebue with deft precision.

The biography follows a broadly chronological structure, tracing Chamisso’s career as a student, a travelling naturalist, and eventually a curator at the Royal Herbarium in Berlin. Of its close to 550 pages of text, 280 are dedicated to his world voyage aboard the Rurik, a proportion that reflects the significance of the journey in both Chamisso’s life and Glaubrecht’s narrative. Given that Chamisso’s life as a "French Prussian by choice" was far from linear – neither his world voyage nor his career as a naturalist followed a predetermined path – the reader gains a nuanced understanding of his life within its broader historical context. Subchapters structure the dense narrative, allowing for brief thematic digressions into early 19th-century social and scientific developments without losing sight of the central storyline.

The main text is followed by 140 pages of appendices, which include timelines of Chamisso's travels, a timeline of Peter Schlemihl’s fictional journey, a reconstruction of Chamisso’s discovery of salps with annotations, a bibliography, and an index of people mentioned. A historical map of his travel route is placed between the cover and the main body of the text, while several colour illustrations in the middle of the book feature drawings and prints from Chamisso’s expedition. These appendices testify to Glaubrecht’s meticulous research and offer a valuable resource for Chamisso studies.

The book addresses an audience not necessarily engaged in literary or historical scholarship. This is reflected in Glaubrecht’s use of accessible explanations for foundational concepts, such as "autograph" (p. 100), as well as his contextualisation of key historical figures and events. The descriptive style and chapter structure aim to make the wealth of information accessible and to introduce readers to the historical realities of Chamisso’s time. In his introduction, Glaubrecht remarks that Chamisso, once prominent in literary studies, has faded from the memory of natural scientists and that researchers have often lacked access to the objects found in Chamisso’s legacy, now held in Berlin and other collections (pp. 21–22). By offering a unique perspective on the history of science, Glaubrecht offers an opportunity for readers to peer over the shoulder of a 19th-century naturalist while his reflections on source work and research give a small glimpse into the challenges and rewards of researching archives and collections in the history of science.

One of Glaubrecht’s greatest strengths is his ability to vividly convey historical context while reflecting on his own research process. The early chapters switch between a lively description of the Kuhnersdorf estate, where Chamisso deepened his botanical knowledge, and Glaubrecht’s personal impressions of the site more than 200 years later. This alternating perspective gives the narrative a sense of immediacy. Glaubrecht also bridges his work to the "material turn" by highlighting previously unknown or overlooked objects. For instance, he introduces readers to carved whale figurines from the ethnological collections in Berlin, made by the Aleuts, to illustrate distinguishing features of different whale species (pp. 304–308). Through these long-forgotten wooden figures, Glaubrecht illustrates how Chamisso devised an innovative means of knowledge transfer that bridged linguistic and epistemic divides, enabling the study of large and elusive animals like whales with the help of local expertise.

The biography’s clarity, shifts in perspective, and compelling narrative style make it an enjoyable and accessible read despite its considerable length. Glaubrecht demonstrates that it is possible to bridge rigorous scholarly research with a narrative style aimed at a general audience. He masterfully intertwines narrative and detail, ensuring that even with the book’s density, it rarely feels long-winded. His clear storytelling guides readers through Chamisso’s life, offering a balanced portrayal of the personal and scientific aspects of the protagonist.

However, the biography is not without its flaws. One point of critique is the repeated invocation of figures like Napoleon Bonaparte and Alexander von Humboldt as reference points for Chamisso’s story. Glaubrecht describes how, on the same day that Napoleon was captured in the port of Rochefort, Chamisso departed from Berlin for St. Petersburg to begin his world voyage aboard the Rurik (p. 125). While these parallels aim to connect Chamisso’s life to larger historical narratives, the frequent use of "anchor points" involving prominent figures can feel forced. This approach, while perhaps intended to sustain reader engagement, risks overemphasising Chamisso’s significance relative to these figures.

It is, of course, legitimate to craft a biography that places a particular figure in the spotlight, examining their actions and legacy. But biographies also offer a chance to illuminate the broader context in which an individual lived. Glaubrecht frequently notes how Chamisso’s scientific training was unusual for someone of his background. Still, he does not elaborate on what this training involved or how it contributed to Chamisso’s development as a naturalist. He addresses Chamisso’s status as an émigré and the associated challenges, but he misses the opportunity to explore how other émigrés contributed to the natural sciences of the 19th century. His discussion of Berlin’s intellectual salons, many of which were hosted by Jewish women, mentions figures like Rahel Levin and briefly hints at the challenges they might have faced, both as women and as Jews, but does not explore how these spaces shaped Chamisso’s intellectual development as a Catholic Frenchman in Berlin’s elite circles.

While the wealth of information leaves no sense of gaps, there remains the feeling of missed potential. Rather than using Chamisso’s position to offer new insights into early 19th-century social and epistemic challenges and important factors often overlooked by grand depictions, Glaubrecht leans on more conventional narratives of discovery voyages and extraordinary individuals.

That said, Glaubrecht’s biography is a masterfully researched and stylistically accessible account of Chamisso’s scientific legacy. Drawing on a unique range of original textual and material sources, the author brings to life the logistical, scientific, and personal dimensions of Chamisso's world voyage. The biography is a significant contribution to Chamisso studies, making this fascinating figure and his legacy accessible to a wide readership. While it could have done more to reflect essential cultural and epistemic aspects of the time by using Chamisso’s experience as a starting point, the biography achieves its aim of bringing a significant figure of 19th-century natural history back into the light. Furthermore, his sharp illumination creates a distinctly three-dimensional image of the French-Prussian naturalist, including his shadow. By thoughtfully combining rigorous source work with vivid storytelling, Glaubrecht offers an accessible yet thorough introduction to the life of Chamisso. For those interested in the history of science, the expeditions of the 19th century, or the practice of scientific discovery, this biography is well worth the read.

Review written by Alexander Stöger

Die Rezension ist unter dem nachfolgenden Link dauerhaft abrufbar:

10.22032/dbt.64194